How we killed the casual artist | Magdalena Styś

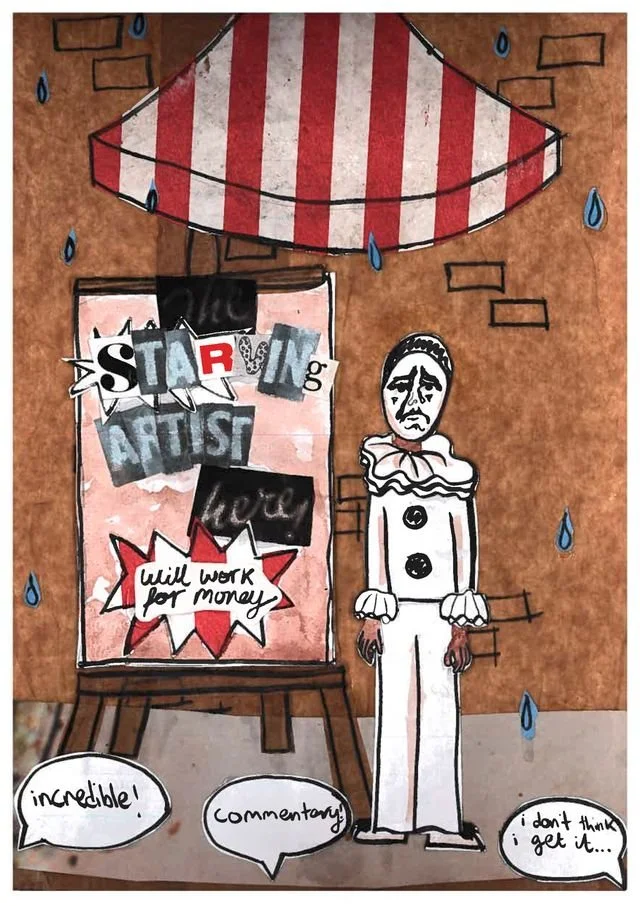

Illustration by Sumaya Moustafa

Whatever vaguely art-and-media-related corner of the Internet you turn to, you’ll find a discussion about the current state of art. Whether asking about the value of human-made art in the age of artificial intelligence, pondering over the ethics of using AI for art at all, or investigating how the online sphere affects our perception of media, you’ll stumble upon a thinkpiece covering every single facet of the evolution of art in the digital space. As brilliant and necessary for the future of art those thinkpieces might be, they primarily focus on what I would refer to as “outward-facing” art (art meant to be consumed,) and on the fate of artworks in general; they don’t mention how the current digital culture affects the process of making art for those of us that aren’t interested in writing the next Odyssey or creating the next Skibidi Toilet — the amateurs, the hobbyists, the casual artists.

We’ve been making art ever since we developed the ability to think and hold tools. If you ever feel like getting sappy on a random Wednesday, Google ‘Cueva de las Manos’ and take a minute (or three hours) to think about how regardless of the time period, the essence of humanity can best be captured by doodling on any doodle-able surface. The vast majority of art created across time was never subjected to the public gaze, and neither was it meant to: the process of creation is valuable regardless of the end product. Making art, regardless of quality, literally enhances your brain function.

Despite the relatively instinctual necessity of art-making for the health of the human spirit and the supposed prioritisation of mental health by the younger generation, there’s little in our culture encouraging casual (not audience-oriented) artmaking. The American Dream and the Boomer concept of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, now repackaged as “hustle culture” or “that girl aesthetic,” linger in the collective psyche, reframing artistic expression as a potential source of income. If you haven’t experienced it yourself, you know someone who has: it’s borderline impossible to express an interest in an artistic pursuit without having someone suggest a way to monetise it. You like editing videos? Why not become a vlogger and get that AdSense revenue! You’re learning to play an instrument? Post some covers on TikTok — maybe you could join the Creator Program! You’re into painting landscapes recently? It’s so easy to start an Etsy shop, really, and I bet you could really make a pretty penny with a good marketing strategy!

Illustration by Sumaya Moustafa

Obviously, this isn’t to say that the increasing number of options for artists to make a living is a bad thing — artists shape the fabric of society and deserve to be compensated for that labour. However, the primary focus on monetisation as an inherent part of art creation reduces art to a more creative form of entrepreneurship and therefore assigns more value to the results than to the process itself. Selling your work requires skill, and if marketability takes center stage in the process of artmaking, daring to do something not “good enough to sell” automatically puts the artistic pursuit up for questioning. In an efficiency-obsessed world, anything that stops the grind is disposable — no shareholder value is increased by my doodles of cats, so why bother?

This obsession with hustling ignores, of course, the fact that most of us don’t really replace leisure time with any sort of grind, but with whatever form of doomscroll is the most popular at a given moment. While this tendency might not necessarily be new — before we scrolled through TikTok, we juggled between TV channels — it is much more surprising when we take into account how ridiculously easy technology makes it to express yourself creatively. The same device that stores our short-form video content also makes it so much easier to create art than ever before, be it visual art, writing, or music — and yet, none of those pursuits wins over the prospect of checking Instagram reels. With each swipe across the screen, the artist within us dies of boredom.

If you were around on the right literary forums at the right time, you’ve read this story approximately three thousand times. In 2006, students from a New York high school sent a letter to Kurt Vonnegut inviting him to visit their class. Although Vonnegut never actually came to the school, he did write back and encouraged the students to make art “no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.” Sure, empty shells might be more productive, but shouldn’t we at least try to act like we’re more than mere physically vulnerable robots?

Letter from Kurt Vonnegut to students (2006)

Overemphasising any activity as the one to finally fix your problems is never useful — painting flower pots won’t save you from your own mind or whatever societal disaster is looming over the horizon. Nevertheless, anything worth doing is worth doing badly, and art is definitely worth doing. Go write a shitty song. I can’t wait to never hear it.

About Magdalena

Any

Magdalena Styś is a writer and poet. Their work has appeared in Also Cool Magazine and the Bitter Melon Review. They’re currently studying linguistics at the University of Amsterdam. Find out more about their work and connect with them below.