In conversation with Faisal Saleh of the Palestine Museum | Bethany Watt

Faisal Saleh, director and founder of the Palestine Museum, invited us to his Edinburgh building to discuss the efforts of his team and the impact of the gallery.

Both the US and Scotland-based galleries host exhibits from Palestinian creatives who are using their art as a form of resistance in the face of genocide.

Upon walking into the museum I was greeted by Faisal, a passionate and caring person who was eager to show me around. The first pieces of art I see are a selection of warped images and paintings; a baby's face with a target on it, another’s with the shadow of a plane covering its mouth, and the red portion of the Palestinian flag dripping down the page as if bleeding out.

The Edinburgh museum took a year to set up after being delayed by COVID-19 and it is a huge success, receiving a minimum of 100 visitors daily. It is hoped that the success of this model can be used for expansion in other countries. Each art piece is unique in conveying its own stories and evoking different emotions, but all work together to scream the same message - Free Palestine. Stop the Genocide.

One of the most popular paintings was pointed out to me. Faisal noted the artist is in Gaza right now. He stated: “This piece was made in 2021, as you could see here, and it basically shows a transfer, a relocation of a sort.

“The artist, in a way, had a premonition almost that this was going to happen. He painted himself three years earlier [as] one of these people roaming around in Gaza being told to evacuate from one place to the next.

“As you can see, the scene there is one of displacement.”

When asked if anyone had heard from the artist recently, Faisal said: “We talk every couple of days; everyone in Gaza is at the end of their rope.”

Pictured below, the painting depicts shadows of faceless people wandering around a vast land of muted colours and a shapeless skyline. A Palestinian’s premonition of homelessness, three years before it struck. It is here, onlooking Mohammed Alhaj’s ‘Forced Evacuation” where we begin the interview.

We start by discussing the goal of Faisal and his team: “Well, the mission of the Palestine Museum is to tell the Palestinian story to a global audience through the arts.

“We want people to know who Palestinians are, what they are like, we are using artwork to tell the Palestinian story.

“As you may know, the western media in general has painted Palestinians in a negative light, often ignoring events that are important [and] only focusing on negative stories of violence and terrorism.

“We are here to change the perspective and the narrative because what is going on now did not just start recently; it’s been going on for one hundred years.

“We are trying to provide a soft approach through art so people can get to know the real Palestine and the real Palestinians.”

Faisal himself is Palestinian, born just few years after what is known as The Nekba or “Catastrophe” as translated from Arabic, referring to the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians. When asked about his childhood and what the displacement looked like he said: “My family comes from a village near Jaffa called Selima.

“In 1948, they were evicted along with seven thousand other people, and they ended up in the West Bank near the town of Ramallah, I was born a few years later.

“My family had ten children, I was the 11th, and we were all living in one room, all thirteen people.

“It was not an easy life, we were living off rations from the UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency) organisation, the one Trump cut funding towards.

“And you know, we made it because some of my brothers started working and supported the family.

“I came to the US in 1969 to finish the last year of high school, and I ended up going to college, I stayed and worked in business for 40-something years before selling my business in 2010.

“A few years later, I created the Palestine Museum in the US.”

Off the back of the huge success of the gallery, I asked if there had been any retaliation in the city since opening the museum: “We've had one incident of vandalism to our sign in the front, you may have noticed that.

“We had a recording of surveillance, a person who walked up the street and walked up the steps, he was wearing an oversized jacket with a hood on it and a mask, although at one point he pulled his hoodie back, and we could see a little bit of his face.

“We intend to provide that [footage] to the police as soon as we complete the report.”

The person had attempted to damage the museum’s sign by writing over it, Faisal added: “But within two minutes of putting that sign on, which was around 11:00 PM on the 27th of July, a young couple walking across the street noticed and they took the sign down. So really nobody saw [what was written].

“The person used crazy glue, and we had a difficult time removing it.

“We decided not to repair the sign and to leave it as a testament to our resilience, we would like people to see it.”

On what he would say to someone who refuses to call what is happening in Gaza a genocide or opposes his work, Faisal replied: “I mean, the whole world knows there is a genocide; anybody at this point who doesn’t think there is a genocide in Gaza must be living on another planet.

“We are very confident in our narrative, so we don’t mind discussing and responding to people.

“In fact, last week we hosted a play called ‘Picking up Stones’, [which] to an extent presented the Israeli narrative with some testament about the Palestinian narrative, yet we allowed it in the museum.

“[We want] people to see we are willing to present opposing views and have no problem responding to them and tolerating the other story.

“Whereas the other people who are opposing Palestine, their only answer is to desecrate our side and vandalise it.”

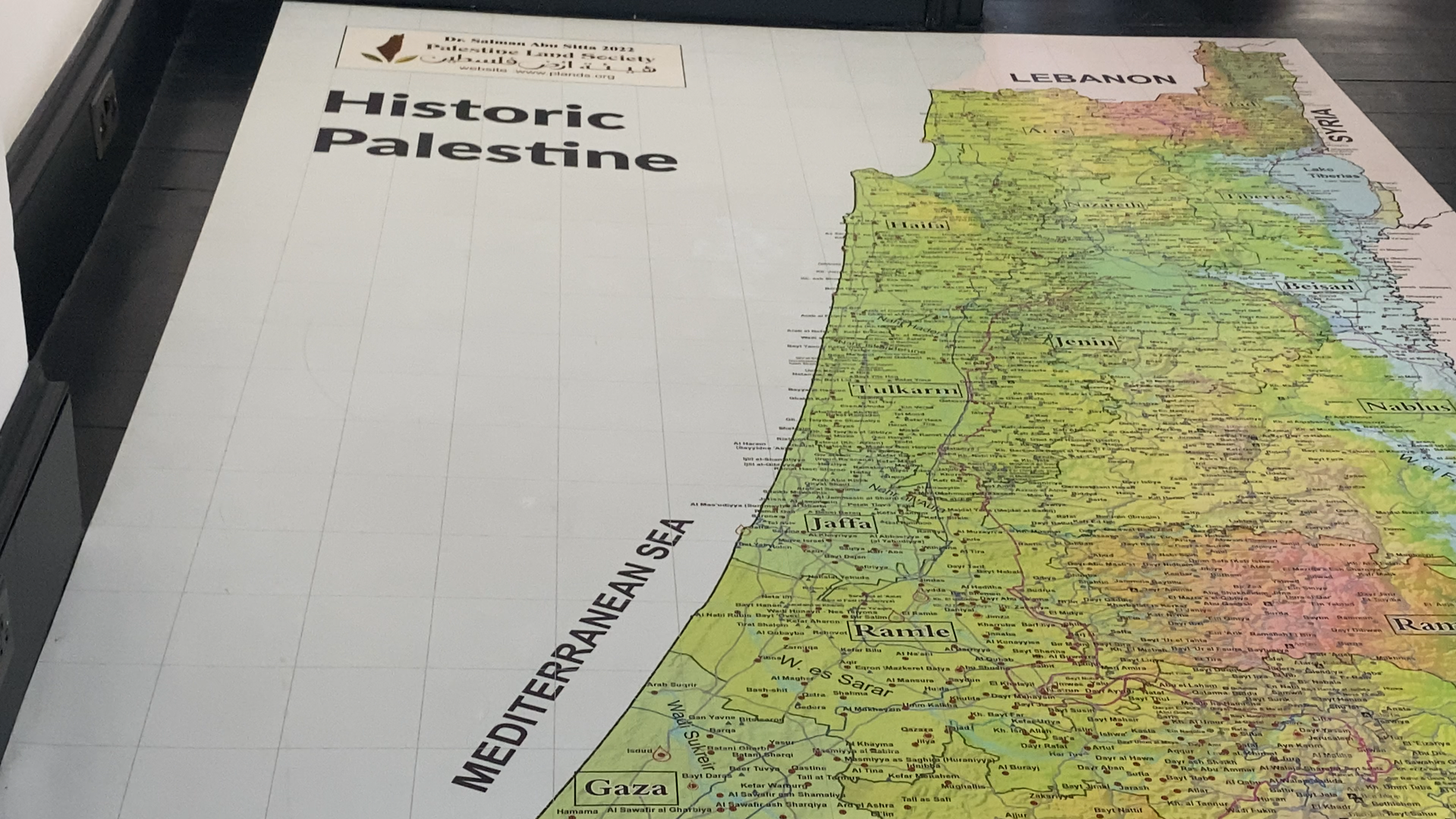

At this point, we moved around the museum, Faisal talked me through what I was seeing, when suddenly he asked me to look down: “We have a map on the floor that shows Palestine in 1948, right before the establishment of the State of Israel.

“Before Israel destroyed and depopulated 500 Palestinian villages and changed their names.

“So, that map kind of preserves the original names and Palestinians can come and recognise their villages, which they can’t do on modern maps that are missing a lot of those villages, and if they are there, they have different names they don't recognise.

“Israel tried to erase Palestine completely, but we are here to show what was there and to present the fact that they exist.”

Standing in this map, surrounded by the artistic manifestations of their pain and suffering, I asked Faisal if he could attempt to encompass what Palestinians are going through in Gaza. You can watch/hear his response below:

Faisal added: “We are back to the Stone Age, except there are no tools, in the Stone Age, they had tools there and things they could do things with, and they could hunt animals.

“The only animals left [in Gaza] are the cats and the dogs, but they are starving those too.”

“Nobody's ever been here before; this is a new level of living that has never existed before.”

It is integral to Disobedient to highlight the atrocities of this genocide in any way we can. We will not stop talking about Palestine, and neither should you.

You can visit the Palestine Museum at 13A Dundas Street in Edinburgh and follow their Instagram page, @palestinemuseumscotland.

About Bethany

She/her

Bethany Watt is Disobedient Magazine’s Current Affairs Editor. She has freelance experience with STV, the Royal Television Society, and the Scottish government. Her favourite subjects to cover include human interest stories, activism, and film. She’s always keen to hear new stories. You can contact her at bethanywatt90@gmail.com